One of my difficulties in attempting to apply non-reductive models of the body to Theosophy is that the tradition and its doctrines, cosmology, and so forth are completely constructed on Cartesian dualism. So frequently Theosophy constructs the mind as eternal and the body as ephemeral. I was reminded of this when perusing a 1916 Theosophical journal this afternoon. In 1916 the Blavatsky Lodge of Theosophists in San Francisco began publishing an independent weekly entitled The Theosophical Outlook. On page three of the first issue is an essay called “Mind and Brain.” Within the essay the anonymous author refutes assertions that injuries to the brain result in injuries to the mind. In the refutation, the author claims that such assertions are similar to saying that a musician, in this case a violinist, ceases to be a violinist when her instrument is broken. The language of the author asserts essences. The musician is a thing, and being in the world which has an ontological status outside of any performative role. The violin is simply the vehicle the musician expresses himself and if broken, it does not affect the musician’s essence. “Understand that the brain is the instrument used by the mind for its manifestation upon this plane of nature in exactly the same way that the violin is the instrument used by the musician for the production of harmonies.” Thus, according to this metaphysical system, depending on the state of the body, the mind can manifest itself properly or improperly, but the state of the body never affects the mind.

The bifurcations and dualisms between essence and extraneousness permeate Theosophy. Yet it is these bifurcations, these underlying dualisms that I want to study but also reject. They are too reductive. The body is reduced to mere happenstance and the mind becomes the house of all being. Instead of this, I want to study the History of Theosophy non-reductively. I want to pay attention to the mind and body of the Theosophists all the while they are claiming the body is not significant and the mind and its spiritual development is all that matters. But doing so is difficult. Since the body is of such little importance, there is little written about actual people’s bodies as they experience their lives. Instead the body is discussed as an abstract object, something to be analyzed and categorized. In discussing the seven principles of the body, the material level is quickly dismissed. It is the other principles that garner focus in the literature, as if there is an assumption that since everyone has physical bodies they interact with, it needs little discussion. However I think this is not true and misses an important aspect of the tradition. As such, when I read Theosophical materials, whether it is periodicals, books, letters or personal diaries, I always have to be on the lookout for the smallest mention of embodied experience. It is usually something small and easily missed. But this close reading begins the processes of entering the embodied world of Theosophy.

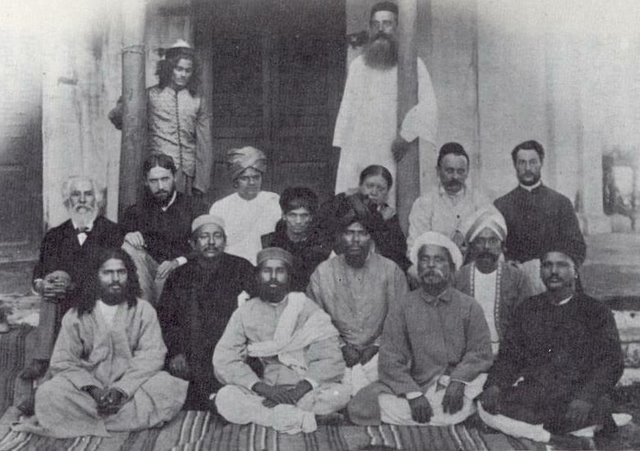

If there is one goal I have in the study in the history of Theosophy it is the unifying of the musician with her instrument. Because it is when the musician and instrument truly become one, it is then that the most beautiful music is made. Similarly, the history of Theosophy resides in the embodied individuals, famous and unknown, who lived Theosophy and made the movement what it was and is today. We cannot separate their minds from their bodies. We cannot look at HPB’s creation of Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine without fully engaging her lived experience as a Russian women traveling throughout the world at a time when being a woman was an obstacle to having ones ideas accepted and taken seriously. We cannot understand the embodied emotions and difficulties Judge experiences when his physical body kept him in the United States when so much of Theosophy’s leadership was in Europe and Asia, and there was so much happening affecting its development and his role in it, an unfolding influenceable only by proxy letter or embodied representatives traveling and debating on his behalf. Lastly, to understand Annie Besant’s struggles, we must not only look at her embodiment at the beginning of the twentieth century, we must take into account her relationships with her children, spouse, and the physical condition experienced in India and the physical toll taken on her by the extensive traveling she undertook. While her mind may have been quite expansive, her body still required her to take planes, trains and automobiles to reach the variety of destinations she visited. In these cases, and many others, individual bodies influenced the development of Theosophy in myriad ways. It is only when we take this into account that we begin to have a richer understanding of Theosophy, and understanding that looks squarely at the time people lived and embodied places the movement developed. It is only then we can close to anything like a comprehensive history of the Theosophical Society, a history that sees the ideas of Theosophy and the people who lived those ideas as one.

Category: Academics, American Religious History, Occultism, Personal Tags: Besant, Blavatsky, Body, Dualisms, Embodiment, Judge, Nineteenth Century, Religious Studies, Theosophical Periodicals, Theosophical Society, Theosophy, Twentieth Century

Comments:

Post a Comment:

| Previous | Mormons, Pagans and ‘Post-Modern Polygamy’ | Blog Posts List | Musings on Bulwer-Lytton, Zanoni, and Fiction as a Source of Theosophical Beliefs | Next |