This weekend, in preparing for my presentation at the AAR, I have been perusing my facsimile prints of The Spiritual Scientist. This newspaper began its life in September 1874 and was published and edited by E. Gerry Brown. It ended publication in July 1878. PDF copies of the newspaper can be found here. The reason I am reviewing it is that prior to the emergence of the Theosophical Society in 1875 and during the Society’s early years, Blavatsky and Olcott were prolific contributors and significantly changed its direction of the newspaper from Spiritualism to Occultism. As a result, its pages contain some of the earliest writings regarding Blavatsky’s ideas about occultism and her efforts to separate occultism from Spiritualism.

While looking through the pages, I could not help notice the numerous instances Bulwer-Lytton’s novel, Zanoni (1842), was mentioned, or had extracts published. For instance, in the June 17, 1875 issue, on the third page in a section entitled “Personal” we read:

Bulwer’s novel “Zanoni,” which is one of the most fascinating he ever wrote, embodies a great deal of information concerning the claims of the occultists which should be read by every intelligent Spiritualist. It is asserted Zanoni and Mejnour are merely pseudonyms for personages who have actually existed and that magical powers were exercised by them quite as remarkable as those attributed to the characters in the book.

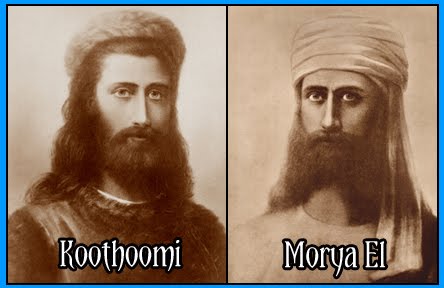

The December 9 issue of the same year has extracts as do other issues of the newspaper. The fiction of Bulwer-Lytton was very influential on Blavatsky and Olcott and the emergence of the “Masters” or “Mahatmas” Koot Hoomi and Morya later seems to be modeled on Zanoni and Mejnour. Other Bulwer-Lytton works that influenced Blavatsky and Theosophy include The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), “Zicci: A Tale” (1838), A Strange Story (1862), and The Coming Race (1871), also known as Vril: The Coming Race. We see reference to these works repeatedly throughout Theosophical literature, as well as assertions that Bulwer-Lytton was a practicing occultist. In Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky mentions Vril repeatedly and claims that it is a cosmic force and power that occultists wield and that Bulwer-Lytton was able to control. Of course the fact that Bulwer-Lytton was not an occultist was not important. For instance, in a letter Bulwer-Lytton claims the Vril of his “Coming Race” was based on his imagination of what electricity could be used for in the future.

The December 9 issue of the same year has extracts as do other issues of the newspaper. The fiction of Bulwer-Lytton was very influential on Blavatsky and Olcott and the emergence of the “Masters” or “Mahatmas” Koot Hoomi and Morya later seems to be modeled on Zanoni and Mejnour. Other Bulwer-Lytton works that influenced Blavatsky and Theosophy include The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), “Zicci: A Tale” (1838), A Strange Story (1862), and The Coming Race (1871), also known as Vril: The Coming Race. We see reference to these works repeatedly throughout Theosophical literature, as well as assertions that Bulwer-Lytton was a practicing occultist. In Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky mentions Vril repeatedly and claims that it is a cosmic force and power that occultists wield and that Bulwer-Lytton was able to control. Of course the fact that Bulwer-Lytton was not an occultist was not important. For instance, in a letter Bulwer-Lytton claims the Vril of his “Coming Race” was based on his imagination of what electricity could be used for in the future.

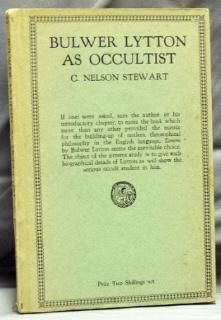

Bulwer-Lytton died in 1873, yet we still see Theosophical claims that Bulwer-Lytton was an occultist well into the 20th century. There was even a book published by the Theosophical Society in 1927 entitled, Bulwer Lytton as Occultist. Written by C. Nelson Stewart, his volume claims, “If one were asked to name the book which more than any other provided a matrix for the building-up of modern theosophical philosophy, Zanoni seems the inevitable choice.” Yet one really must look too many of Bulwer-Lytton’s works, because they influenced Theosophy in myriad ways. Yet proving their influence is difficult. Moreover, to what end? What do we learn from pointing out the influences?

Bulwer-Lytton died in 1873, yet we still see Theosophical claims that Bulwer-Lytton was an occultist well into the 20th century. There was even a book published by the Theosophical Society in 1927 entitled, Bulwer Lytton as Occultist. Written by C. Nelson Stewart, his volume claims, “If one were asked to name the book which more than any other provided a matrix for the building-up of modern theosophical philosophy, Zanoni seems the inevitable choice.” Yet one really must look too many of Bulwer-Lytton’s works, because they influenced Theosophy in myriad ways. Yet proving their influence is difficult. Moreover, to what end? What do we learn from pointing out the influences?

In his recent review of Brill’s Handbook of Contemporary Paganism, Markus Altena Davidsen writes that the volume lacked acknowledgement of the ways fiction and other media, such as movies and television shows, have greatly influenced modern paganism. This lack of engagement, however, is also present in the study of victorian occultism. While it may be easier to point to the way Heinlein’s A Stranger in a Strange Land was influential on the pagan Church of All Worlds, it is harder to pin-point direct influences in the doctrines of Theosophy because Blavatsky and others both intentionally obfuscated influences, and also invented ideas about the works and person of Bulwer-Lytton. So how are we, as scholars, to address these issues? When Blavatsky writes,

If the question is asked why Mr. Keely was not allowed to pass a certain limit, the answer is easy; because that which he has unconsciously discovered, is the terrible sidereal Force, known to, and named by the Atlanteans MASH-MAK, and by the Aryan Rishis in their Ashtar Vidya by a name that we do not like to give. It is the vril of Bulwer Lytton’s “Coming Race,” and of the coming races of our mankind. The name vril may be a fiction; the Force itself is a fact doubted as little in India as the existence itself of their Rishis, since it is mentioned in all the secret works.

Do we simply claim she was myth-making based on Bulwer-Lytton’s fiction? Okay, maybe that is true. But so what? Blavatsky’s assertion informs Theosophical Doctrine and many Theosophists take these statements as fact. Stewart claims that Zicci and A Strange Story “were based rather upon what we should now call ‘astral experiences’ beginning in [Bulwer-Lytton’s] early youth.” In all these Theosophical assertions, fiction acts to reveal and conceal what Theosophists see as occult truth. Those who have the eyes to see and can read between the lines see in Bulwer-Lytton’s fiction the truth of occultism and the works become manuals. Terms such as “The Dweller on the Threshold” enter occultism and become topics of Theosophical doctrine. Fiction becomes the seeds that sprout into assertions about occult truth. So what?

To date the only sustained scholarship about the influence of Bulwer-Lytton on Theosophy is S.B. Liljegren’s Bulwer Lytton’s Novels and Isis Unveiled (1957). Robert Lee Wolff also makes a few references to Theosophy in a chapter in his Strange Stories: Explorations in Victorian Fiction—The Occult and the Neurotic (1971). Yet, both of these works are very old and the topic could benefit greatly from more recent scholarship in both Victorian occultism and English literature. But despite these two instances, there is still something in me that thinks there is more to be said that simply pointing to Bulwer-Lytton’s influences. I keep asking, “So what?” Writing that Blavatsky’s masters were fiction is not new, the Hodgson report was claiming that over a century ago. So does it matter that Bulwer-Lytton’s Zanoni and Mejnour were her models for masters? I am not interested in participating in claims of legitimacy, an issue that is probably at play in the essay on paganism Davidsen reviewed. So how does the mentioning of the fictional origins of Theosophical doctrine advance scholarship? At this point, I’m not sure. I keep asking, “so what?” I am sure fiction played a role in Theosophical doctrine. Now what? This is now something I am still considering.

Category: Academics, Occultism, Western Esotericism Tags: Books, bulwer-lytton, fiction, Nineteenth Century, occultism, spiritual scientist, spiritualism, Theosophical Society, Theosophy, Twentieth Century, zanoni

Comments:

Franklin, December 3, 2012 at 4:25 pm

I have been a student of occultism for most of my life and am very familiar with Zanoni and Rosicrucianism. It has always appeared to me that theosophy was the new age religion of the 19th century, a faddish movement that borrowed elements of Rosicrucianism, spiritualism, freemasonry, and a host of other subjects. Your assertion that Zanoni could have influenced theosophic writers is quite possible because theosophists were prone to exaggerate and embellish a great deal. I think you are on the mark here. However, you are wrong to state that Bulwer-Lytton was not an occultist. Occult studies was one of his huge passions. Also, Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism existed well before theosophy.

LG, December 14, 2013 at 3:27 pm

Friend, your article and research raises many interesting points for discussion. However, I feel in my heart that understanding the doctrines instead of analyzing them will satisfy the need for the questions posed above.

– “How does the mentioning of the fictional origins of Theosophical doctrine advance scholarship?”

Here is implied theosophical doctrine in the sense of the Modern Theosophical Movement (spear headed by Blavatsky and co.). The doctrine itself states it is much older and found throughout all the worlds religions. You know all of this. Therefore, if founded on the eternal verities, how can any incarnation of a theosophical doctrine have for itself fictional origins? Teachings indicate the astral body to predate the physical one. You know this. The same analogy for fiction in occult writing.

– “Of course the fact that Bulwer-Lytton was not an occultist was not important. For instance, in a letter Bulwer-Lytton claims the Vril of his “Coming Race” was based on his imagination of what electricity could be used for in the future….We still see Theosophical claims that Bulwer-Lytton was an occultist.”

Bulwer-Lytton was himself a part of the ‘theosophists of the ages’ evident by the truths scattered in his writings and found in all great works known to man. In Zanoni, it is asserted that no idea is original. Essentially, a statement from someone acquainted with the teachings of Paracelsus who is mentioned by name in the occult tale as well. Bulwer-Lytton published a poem on Freemasonry, “The Mystic Art.” It is wildly apparent to anyone who has studied occultism with half a brain that Bulwer-Lytton was initiated in the mysteries and had access to inner teachings. All biographies are mute on this issue or make claims which are reduced to mere speculation. And rightfully so! Truly, a toast to the genius and true occult nature of the life of the Baron whom leads by example through teaching others via his ideas and not by his personal life. This is dually noted between the dialogues of Zanoni and Mejnour as to which lifestyle of an “Adept” is most appropriate in addition to the secrecy vows of pledged members of a Rosicrucian order.

Blavatsky herself states many times her ideas are not original, but instead that she took the roses from around the world’s cultures, sciences, religions, philosophies, etc. and tied the bouquet together just as many have done previously. The concept of Masters existed before the TS, before Zanoni, and will exist long after the TS and Zanoni are forgotten.

Musing over fiction as a source of theosophical beliefs is an offense to the sincerity of any minds honest in their study of occultism, be it whatever path. It perfectly represents the TS’ modern reversal and continued unfamiliarity to the sources and writers which brought to the 19th century an updated understanding of its namesake while it chases weekly after the very pseudo-sciences its society’s founders sought to dispel. It is amusing only to the equally offensive placement of M. to the right of KH.

Such are the blinds and disadvantages to those who study the material for commentary and scholarship, instead of for themselves to use it to better enable themselves to help and teach others in service of the fellow man.

Maureen Richmond, March 22, 2016 at 12:31 pm

Weighing in here is M, Temple Richmond, author of Sirius, scholar of the Theosophical and Alice Bailey literatures, and graduate student in English and Creative Writing.

I believe there is a fundamental mistake in interpretation of a key Blavatsky statement by the owner of this site, John Crow. Here is the statement, which I copy and paste from above:

“If the question is asked why Mr. Keely was not allowed to pass a certain limit, the answer is easy; because that which he has unconsciously discovered, is the terrible sidereal Force, known to, and named by the Atlanteans MASH-MAK, and by the Aryan Rishis in their Ashtar Vidya by a name that we do not like to give. It is the vril of Bulwer Lytton’s “Coming Race,” and of the coming races of our mankind. The name vril may be a fiction; the Force itself is a fact doubted as little in India as the existence itself of their Rishis, since it is mentioned in all the secret works.”

In this passage, HPB is neither stating nor implying that the source of her notion about a cosmic electrical power is Bulwer-Lytton’s vril, but rather she is using what was at the time a contemporaneous literary example to give clarity to the people of that day in regard to her meaning. It would be as if in the twenty-first century some spiritual teacher said of telepathy, “It’s like the internet, you see, where information is transmitted instantaneously from one mind to another.” In two hundred years, a reader of that statement could, as did John Crow, mistake the meaning to be that telepathy was dreamed up after the internet was invented. As is clear to us now because we exist in this internet time, that’s not the case. The notion of telepathy existed first; then along came the internet.

In the HPB passage pasted here from John Crow’s essay, Blavatsky’s meaning is quite simple. She’s just using what was at that time a popular literary work to illustrate her point.

However, I understand John Crow’s apparent interest in getting at the sources of the Theosophical Tradition. These sources are outlined in two of the comment posts entered before mine. I think Mr. Crow should read more actual text by HPB, as one of the other commentators suggests, to see that HPB did not claim novelty for her teachings – in fact, quite the opposite. Further, the fact that the Rosicrucian tradition may have been the apparent source of any of her ideas fails also as an accusation of inauthenticity, because HPB contended all along that the Ancient Wisdom Teaching is one river with many sources. Rosicrucianism was one of those.

Maureen Temple Richmond

Burlington, NC, USA March 23, 2016

Pingback: Theosophy, Zanoni, the Occult Law and the Golden Age - Worldwide Ashram Blog

Post a Comment:

| Previous | Attempting to Unify the Musician and Her Instrument | Blog Posts List | The Strange Theosophical Connection to the U.S. Civil Rights Movement | Next |